9th Tape College highlight: why silicone PSAs “are quite unusual”

At Afera’s recent 9th edition of the Tape College in Brussels, popular presenter Alex Knott provided an introduction to silicone PSAs and fluorosilicone release coatings. Mr. Knott, who is a senior scientist at The Dow Chemical Company, related that more people in the tape industry are becoming familiar with silicones. These are best known in the adhesive tape market as release coatings, but there are also PSAs based on silicone that are used for special applications in which very specific performances are required.

At Afera’s recent 9th edition of the Tape College in Brussels, popular presenter Alex Knott provided an introduction to silicone PSAs and fluorosilicone release coatings. Mr. Knott, who is a senior scientist at The Dow Chemical Company, related that more people in the tape industry are becoming familiar with silicones. These are best known in the adhesive tape market as release coatings, but there are also PSAs based on silicone that are used for special applications in which very specific performances are required.

Increasing use in electronics markets

Silicone PSAs are not widely used, because they are more expensive than organic PSAs, but they are sought after for their high-temperature performance, chemical resistance, adhesion to low-energy surfaces, flexibility, weatherability, clean removability, and insular and vibration damping properties.

Silicone PSAs are mainly used in masking tapes for electronic PCB and chip processes, in which masking tapes are applied to a printed circuit board, a part of the chip manufacture or the wafer on the holder during processing. In these cases, a very quick and stable level of adhesion is required. Asia utilises silicones for this application the most, although Europe’s activity in this area is picking up.

Another trend in Asia that is picking up in Europe too is the use of silicone PSAs in optical devices, i.e. for bonding glass or foam or different laminates together within in all kinds of mobile devices. This application calls for adhesive tapes which are optically clear, will exhibit consistent properties over a long period of time, and are flexible to adhere to electronics in different stages of use.

Because of the trend toward making devices thinner, heat management, flexibility and other physical properties of the PSA are becoming increasingly important. “Tape is no longer simply a layer that is bonding 2 rigid surfaces together, it is now playing a part in the whole structure of the material,” Mr. Knott explained.

Why they’re special

Why they’re special

The chemistry involves using 2 raw materials: a resin based on a silicate (MQ) and a silicone polymer (typically dimethyl-functional but vinyl or phenyl groups can also be added) mixed in a solvent. This is then crosslinked for strength using one of 2 technologies to produce peroxide-curable PSAs, which are more common because their thermal stability tends to be better, and addition-cure PSAs.

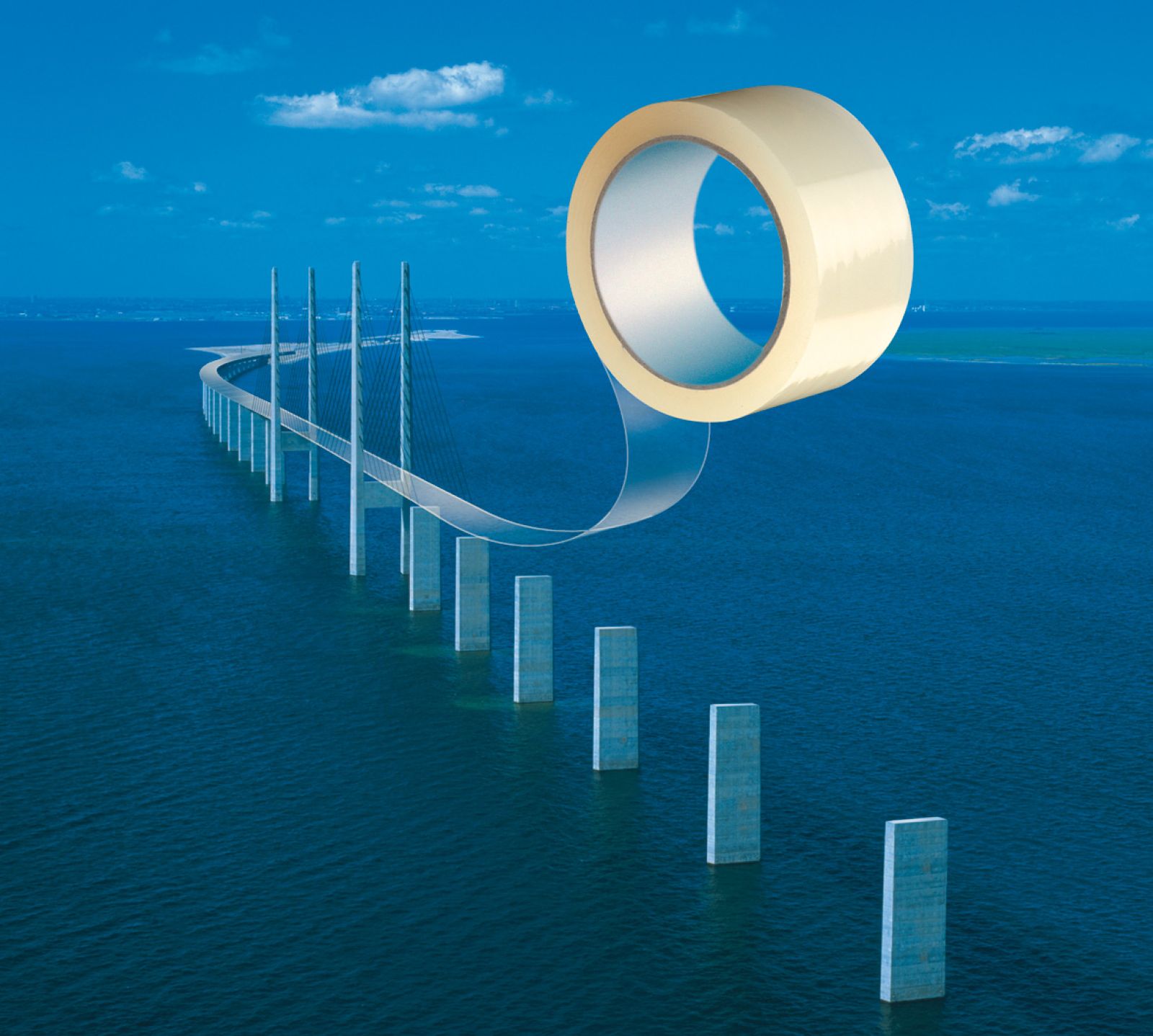

“Silicone PSAs are quite unusual, because they have a range of different formulations that stick to a variety of surfaces, such as HDPE, glass and aluminium, with the same levels of adhesion,” said Mr. Knott. “This can be a disadvantage if you are looking for very high adhesion, but it can be a great asset if you just want to formulate for a certain level of adhesive regardless of the surface it ends up being stuck upon.”

What did attendees take away?

The adhesive properties of silicone PSAs are determined by the resin-to-polymer ratio, a very narrow window in which a sticky material is created. If you have a very low level of resin, you won’t have a PSA at all as it won’t be sticky enough. The result will be dry and have a low tack, low adhesion and almost no cohesive strength, resembling a silicone release coating. If you add more resin, you will reach a peak level of tack, creating a sticky mass with only a modest level of cohesive strength. Add even more, and you will drive it to very high levels of cohesion, but too much resin will result in an almost glassy coating on the surface.

Many silicones do not require release liners, but for those that do, traditional liners with coatings based on dimethylsilicone will not work as they will not bond and release. Instead, fluorosilicone release coatings are required. Dry lamination works very well, whereas wet lamination can become complicated.

Learn more about Afera’s Tape College

Register for Afera’s upcoming Lisbon Conference

Learn more about Afera membership